For George Miller, an Australian director, it took a lot of work and a lot of yearning to make “Three thousand years of longing,”, his long-awaited sequel to “Mad Max Fury Road”.

Miller’s “Three Thousand Years of Longing,” which was premiered at the Cannes Film Festival over the weekend, is the culmination of a journey that began twenty years ago when Miller read “The Djinn In The Nightingale’s Eye” by A. S. Byatt.

It was only after frictions over profits from Miller’s operatic action opus “Fury Road”, that Miller opened the door to “Three Thousand Years of Longing.”

Miller, who was speaking alongside Tilda Swinton and Idris Elba shortly before the Cannes premiere of the film, said, “After we wrote, it was really just a matter of when it would be done.” It was actually a lucky film. “We got into litigation with Warner Bros. regarding ‘Fury Road’. It meant that we could bring this to the forefront.

Most Cannes festivalgoers were on the edge of their seats when “Three Thousand Years of Longing” was revealed. What could Miller conjure up? Can the 77-year-old filmmaker match the exhilarating thrill of “Mad Max Fury Road?”

Miller is planning to revisit the film with the prequel “Furiosa” seven years ago. Its blistering Cannes premiere was a landmark in Cannes. The film went on to win an impressive number of Oscars, $374million in box office receipts, and a spot on many best-century lists.

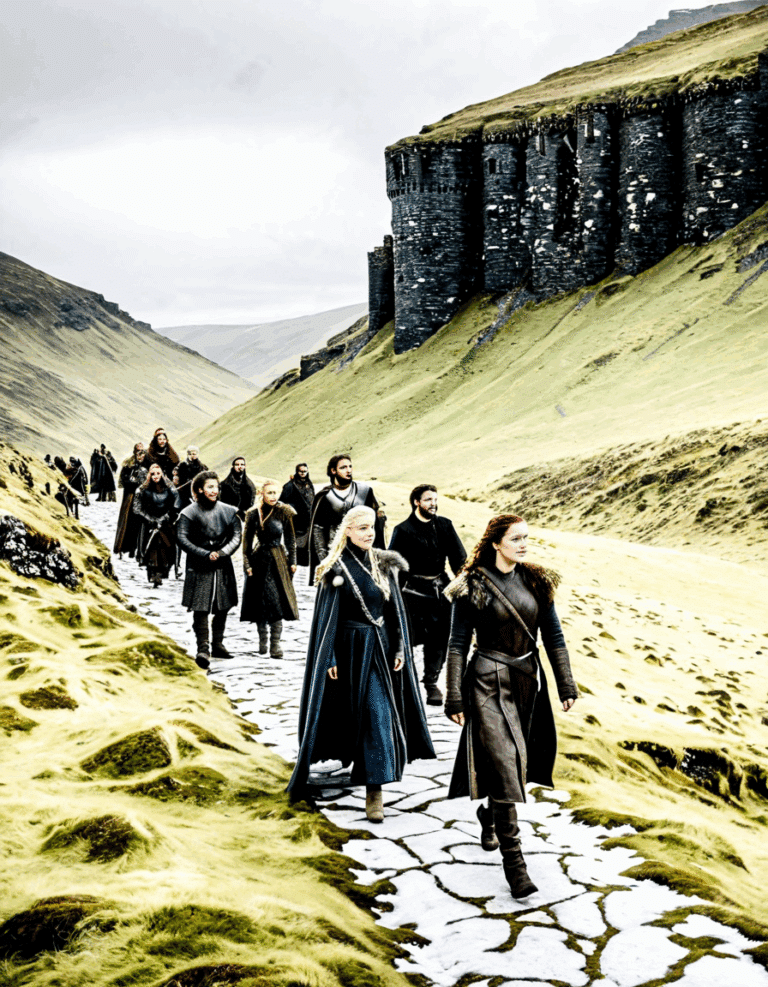

It turns out that the answer is a unique blend of chamber-piece drama and fantasy epics that speaks to Miller’s feelings about storytelling. Miller and Augusta Gore, Miller’s first screenwriter, wrote the script. Swinton portrays Alithea Binnie, a narratologist who visits Turkey to speak at a conference about how science has replaced mythology.

Alithea purchases an old bottle from the Grand Bazaar and then scrubs it in the hotel sink. A wish-granting djinn, Elba, appears filling the room. He then has an intimate conversation with Alithea, where he shares stories about his masters over the past 3,000 years. Miller uses computer-generated imagery to blend mythology with the modern world in a historical fairy tale that is contemplative and rooted in magic.

Miller states that Miller is one of those people who can tell stories as a performance. “I know I struggle with this. I struggle to tell spontaneous stories well. However, I can tell a movie in slow motion, where I consider every nuance and every rhythm.

Miller again teamed up with his “Fury Road” collaborators, including John Seale, Margaret Sixel, and Tom Holkenborg, the cinematographer. The director realized that “Three Thousand Years of Longing”, in some ways, was the “anti-Mad Max,” a talkative film whereas “Fury Road,” was not wordless and spread over eons instead of in real-time.

Although reactions to “Three Thousand Years of Longing” have been mixed, few people have doubted its ambition or uniqueness.

The movie covers all eras and still holds true to the present day. In scenes in which background actors wear masks, the pandemic is shown late in the movie. Dramatically, the pandemic also shaped the film’s production. Miller switched from filming in several international locations to relying on CGI, and his native Australia for most of the film.

Swinton states, “When we started talking about this movie, it felt very natural.” It’s even better this year. It will only get better the next year, I think. Your instinct for the wind is going to run and continue. It’s like planting a seed.

Miller says that “Three Thousand Years of Longing,” doesn’t end with the present, but goes beyond.

Miller says, “It’s an extremely pertinent story.” Miller says, “It’s a Geiger counter or metal detector that activates when there is something.” “Oh, there is a rich seam here.

“Time will show if there is enough content in it for other people to respond to it.” He said that he hoped the story would be shared with others and become a common one.